Some things that scientists can learn from the arts

Artists and scientists have more in common than you may think

Knowledge isn’t easy to classify. Where does mathematics finish and physics begin? What about the boundary between biology and chemistry? After all, our taxonomy of knowledge is more a practical than a descriptive one: it allows us to compose the academic syllabi with something more detailed and informative than knowledge 101, knowledge 102, and so on.

While some boundaries between disciplines are fuzzy, others seem to be crystal clear. One of the less disputed ones is that between arts and sciences. The difference seems to be so clear that artists and scientists are often presented as opposite and even irreconcilable characters. But this border is also diffuse and permeable. A lot has been said, for instance, about the contribution of science to the arts through new materials and technologies, and arts are often mentioned as a source of inspiration for science.

And therein lies the rub. All that talk about “inspiration” sounds subtle, almost esoteric, and many scientists will raise their eyebrows when hearing about it. But what if I tell you that during my (still young) scientific career I’ve found that the arts, apart from being pleasant and enjoyable, have provided me with some useful tools for my everyday work as a scientist.

With this small list, I hope to convince even the most pragmatic of readers.

Literature

Writing is one of the main activities of any scientific researcher. Basic knowledge of different writing styles and strategies can be very useful. It is true that scientific publications tend to use a very odd style (so odd that sometimes it is hard to believe that they have been written by a human being). Very often the scientific writer is forced to follow this odd style, why then learn about different writing styles?

Well, for a start, scientists write more than papers. They also compose emails, press releases, blogs, posters… Each of these formats has its own style. Strange things may happen when the “scientific paper style” is used for something else, such as a marriage proposal.

The best way of improving your writing style is to read people who write well. A very pleasant way indeed.

Performing arts

Think of a scientific conference you’ve recently attended. Ask yourself how many talks you remember and why. Very often, your memory will be triggered by something not fundamental to the talk, such as a great explanation of a known concept or a really funny joke.

In any talk, the presenter’s speaking skills are as relevant as the content itself. A talk with good content but filled with hesitation and anxiety can become almost painful to watch for the audience. On the other hand, a talk with more humble contents but with a brilliant speaker will (at least) be remembered when the congress finishes.

Not paying attention to the cues of the audience, being unable to dynamically adapt the relative importance of each section, speaking too softly or being long-winded, all of these are subtle details that can ruin a talk within minutes.

Some basic notions of theater, storytelling, timing and audience engagement (magic is great for this) can be very helpful.

To quoting The Simpsons: “Every good scientist is half B. F. Skinner and half P. T. Barnum.”

Graphic design

Do you know what a graphic designer’s worst nightmare is? To be locked in a room during a scientific poster session. Slides can also be quite terrifying for them.

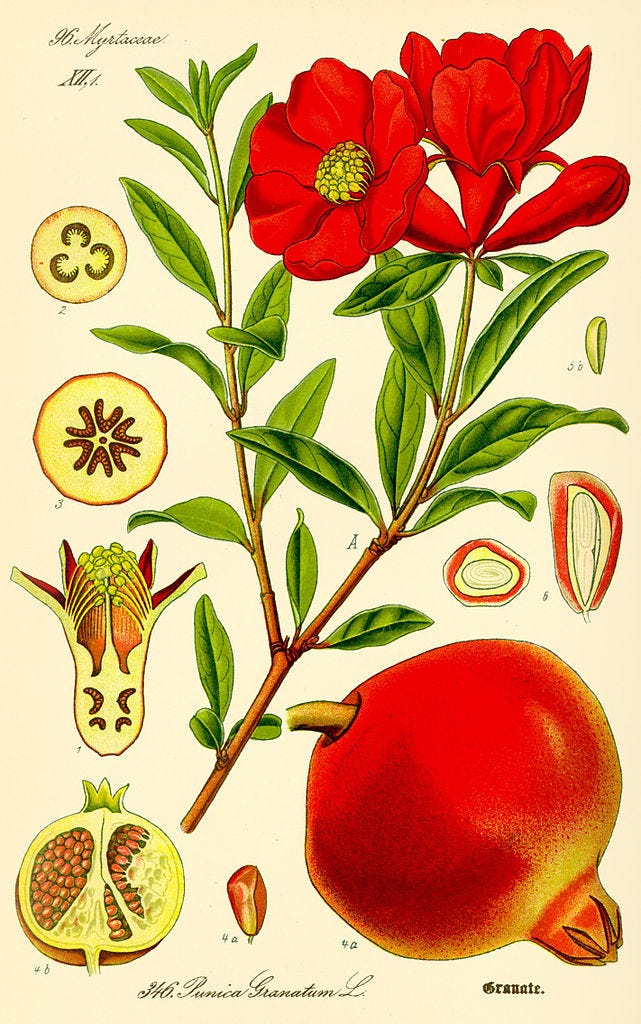

Scientists use visual tools all the time. Figures, plots, tables — not to mention there are even artistic sub-genres such as technical and naturalist illustration. But scientists rarely receive specific training in the appropriate use of these visual tools.

Most people (and scientists are no exception) don’t know that there are certain rules about design. Some of them are subtle, such as not using the same figures in a paper and in a poster or slides (each format should be read from a different distance, and with a different level of attention). Others are well known, but very often broken for no good reason (such as minimizing the use of text or using a proper font size). Last but not least, there are mistakes so obvious that it is surprising they still persist (such as using crazy color combinations or adding a slide with 25 references… that will remain on screen for 3 seconds).

A personal tip: a few years ago, I collaborated with the human resources department of a tech company. We spent several days reading the curricula of mathematicians, physicists and engineers. I cannot stress enough the strategic advantage of having an aesthetically, well-designed curriculum.

Spending some time learning the basics of visual communication will definitely pay off.

Understanding creativity

Another shared feature of scientists and artists is that they both have creative jobs.

Understanding how creative processes work is more complicated than it may seem. We, scientists, tend to struggle with the fact that hitting our head against a problem when we are blocked rarely gives any result. Even worse, it is usually counterproductive. Often, the best way to find a solution is to explore alternative paths, or even abandon the lab and go for a walk, do some sports or just have a beer.

In the world of arts, traditionally more bohemian, everybody is aware of this. To the point that, for instance, some design agencies implement protocols to guarantee that several options are always explored before choosing one at the beginning of a project.

And that’s it for now. Feel free to add your own experiences in the comments section below.

References

- The craft of scientific writing. Michael Alley.

- The craft of scientific presentations. Michael Alley.

- The art and science of data visualization, Moritz Stefaner

- How small changes to a paper can help to smooth the review process. Nature

- Novelist Cormac McCarthy’s tips on how to write a great science paper. Nature

- Want to be More Creative? Take a Walk. Gretchen Reynolds. The New York Times.

- Try, try again? Study says no: Trying harder makes it more difficult to learn some aspects of language, neuroscientists find. Anne Trafton. Science daily.

This blog entry is adapted from its Spanish version, that appeared first in Naukas